Evolution of Web and the QUIC protocol

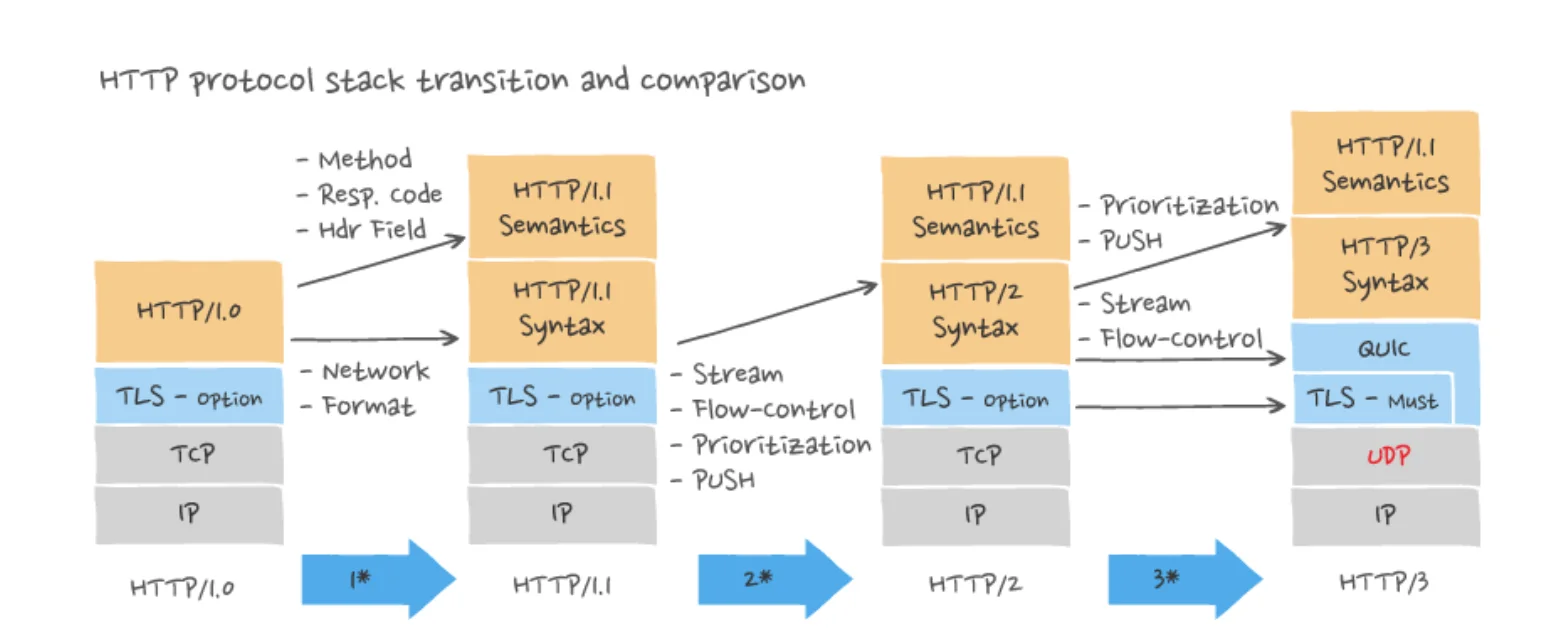

This section reviews the evolution of World-wide Web and the HTTP protocol from the beginning in the 1990s until today. For long time, HTTP/1.1 was the transmission protocol for web content and web-based applications, but more recently there has been more rapid development of HTTP. The current version, HTTP/3 is rather different from the original, and can be thought of as a more general transport platform for different kinds of applications.

In this section we

Review the early versions of HTTP and remind ourselves about its capabilities and limitations.

Discuss the security of the web protocols, and application protocols in general based on the TLS protocol.

Discuss the performance aspects and limitations of web communication.

Get familiar with HTTP/2, which is a rather radical redesign of the HTTP protocol over TCP.

Get familiar with HTTP/3 and QUIC that is a new transport protocol built on top of UDP, aiming to address the performance and security limitations of earlier HTTP versions. QUIC could also be used for other upper-layer protocols than HTTP.

Discuss some different applications that HTTP/3 and QUIC enables, and the ongoing work in the IETF on these topics.

Related assignment: “Experimenting with QUIC”

The below illustration is taken from a blog article by Ably discussing the latest versions of HTTP.

Early versions of HTTP

World-Wide Web and the Hypertext Transport Protocol (HTTP) were published in 1991 by Tim Berners-Lee and group of CERN researchers. The original version (HTTP/0.9) was only designed to fetch static text and image content for rather simple (in current web standards) pages. Only GET request was supported, and a separate TCP connection was opened for each object. Note that at the time TCP and its congestion control was much less optimized than what discussed in congestion control section, but on the other hand, also the web content was simpler and smaller in size.

Few years later, HTTP/1.0 was released in 1996. It added the POST method, for sending data also from the WWW client to the server, and introduced various key concepts, such as HTTP headers and return codes. Importantly, HTTP/1.0 introduced Content-Type header, that enabled transferring also other types of content than HTML files for transferring “hypertext” with links to other content.

HTTP/1.1

HTTP version 1.1 was the first version standardized by the IETF (originally RFC 2068, current version RFC 9112). It introduced the remaining methods needed to enable REST APIs, such as DELETE and PUT, and enabled wide-spread use of the HTTP protocol for not only transferring static content but as a platform for web-based dynamic applications.

Among many improvements, HTTP/1.1 introduced more efficient ways of using the underlying TCP connections. Unlike in earlier versions, that opened a new TCP connection for each HTTP request, HTTP/1.1 allows persistent connections, i.e., re-using the same TCP connection for multiple HTTP requests and responses. This increases the communication performance, because the three-way connection establishment handshake is not needed for every object, and the congestion window has time to grow into appropriate size, instead of having to go through slow-start for every web object.

HTTP/1.1 also introduced HTTP pipelining, the possibility to send multiple HTTP requests back-to-back, before receiving the responses. Because TCP is stream-oriented protocol that does not preserve message boundaries, the response headers need to indicate the length of HTTP payload, so that the client knows where the next response begins. With pipelining the responses also need to arrive at the same order in which the requests were sent, so that they can be matched with correct request. In practice HTTP pipelining is not used, however. Many network proxies and other devices do not support them, and break the message exchange. Also the strict in-order delivery causes performance challenges, if the objects have different sizes or cache properties: a slow first object delays the delivery of later objects, even if they were faster delivered.

Challenges with HTTP/1.1

Even though for efficiency it is a good idea to reuse the same TCP connection for multiple HTTP requests and responses, it has its challenges. Particularly, because TCP’s semantics promise reliable in-order delivery of a continuous byte stream, packet loss and subsequent delay in TCP transfer holds the transmission of all following HTTP requests and responses, until the data can be successfully delivered. This is called head-of-line blocking. HTTP clients have mitigated this issue by opening multiple TCP connections in parallel, and pooling to requests over them. This way a problem in one connection does not block the transmission on others. Using parallel TCP connections is not ideal though: each connection maintains its own congestion control and in principle can gain unfair proportion of the available network capacity from other applications that appropriately use only single TCP connection for their traffic.

Further reading

- T. Berners-Lee, R. Cailliau, A. Luotonen, H. Frystyk Nielsen, A. Secret. The World Wide Web. Communications of the ACM, vol. 37, n. 8, August 1994.

TLS and performance effects

Like many other Internet protocols, also HTTP was designed without security capabilities. The messages and their content is readable by any intermediary device that can detect and process the IP packets on the communication path. This might have been acceptable in the old days, when Internet was mostly in academic use, but now that e.g. HTTP is used for many business critical applications from banking to health services, it is essential that the communication is secured.

Transport layer security (TLS) has become a common standard in securing the communication in application protocols such as HTTP and many others. It works on top of the TCP protocol: after TCP connection establishment handshake is complete, the TLS handshake is started to exchange certificate information and session keys for securing communication for the particular connection. This needs to be done separately for every connection, of which there are several with HTTP. In earlier versions of the TLS protocol, the handshake typically added two round-trip times delay before the actual HTTP request could be sent over the encrypted channel. Considering that HTTP typically uses many connections, and many of the objects are rather small, this is is proportionally significant delay.

TLS version 1.3 reduces this delay to one round-trip time in common cases, which improves the HTTP communication performance.

Because of the nature of the HTTP protocol, in which many connections are used, but many of the connections are quite short lived, network delay is the dominating factor in user experience: even though the available communication bandwidth was high, the users’ experience is determined how much delay there is in getting the web content available on the browser screen. Therefore the performance optimizations have focused on reducing the needed round-trips in communication: optimizations to TCP and TLS handshake (e.g., TCP Fast Open, RFC 7413) are one part of this work, increasing TCP’s initial congestion window is another.

HTTP/2

HTTP/1.1 served the web users for a long time since the 1990s, but as the web communication has become more media-rich and interactive, the limitations of HTTP/1.1 started become more pressing. HTTP/2 was a significant redesign of the HTTP protocol, aiming solve the shortcomings of the earlier version. It is specified in RFC 9113.

Unlike HTTP/1.1 and many other older internet protocols, HTTP/2 is a binary protocol that applies HPAC compression (RFC 7541) on the HTTP headers. With smaller headers the network overhead is smaller and communication more efficient. HTTP/2 also introduces server push, a mechanism for sending resources from server without waiting for request from client. The web content typically consists of related files (CSS styles, JavaScript, HTML content) that the server can easily predict as something needed by the client. By doing this, the server can reduce the number of round-trip times needed to produce a web page.

Streams and frames

A significant redesign in HTTP/2 protocol is the distribution of communication into streams, and thereby reduce the number of needed TCP connections. HTTP/1.1 unsuccessfully tried to do the same by applying pipelining to reduce the number of simultaneous connections, but pipelining was not adopted in widespread use due to performance and robustness problems. In HTTP/2 the different web objects are assigned to dedicated streams that can be multiplexed into the same TCP connection. The communication within the connection is split into frames of limited size, which means that transmission of larger objects can be interleaved with smaller objects ensuring more timely delivery, which was one of the problems with pipelining. The streams and frames are assigned priorities, which allows for giving preference to resources that are more urgent to be delivered.

Negotiating HTTP version

In practice HTTP/2 is always TLS-encrypted and it uses the same HTTPS port as HTTP/1.1, TCP port 443. Initially the communication starts using HTTP/1.1 and the client can propose using HTTP/2 using an Upgrade header. There is a negotiation protocol based on Upgrade header in the first HTTP request. If the server supports it, the replies with HTTP/2 “101 Switching protocols” response. Otherwise it responds with “200 OK”, and the communication continues with HTTP/1.1.

There are also optimizations for the negotiation. Application Layer Protocol Negotiation (ALPN) (RFC 7301), allows integrating the HTTP protocol negotiation into TLS handshake ClientHello/ServerHello message exchange. If ALPN indicates that HTTP/2 is available, the client can directly start with HTTP/2 request.

Also DNS was extended with a new resource record type that allows hinting which protocol versions are supported by the server. The HTTPS record type (RFC 9460) allows telling with HTTP versions (and TCP ports) are used for the HTTP service on the particular server, along with background servers for failure tolerance. This way the client can learn the correct version already when doing name resolution.

HTTP/3

HTTP/2 was a significant improvement over earlier versions of HTTP, allowing an efficient way of multiplexing the HTTP content in binary format in single TCP connection. However, the use of TCP still remains potential bottleneck, when transmitting time-sensitive content: TCP promises congestion controlled, in-order delivery of sequence of bytes. If there are packet losses or other disruptions in communication, the retransmissions and possible consecutive timeouts block the transmission of following data, even if only single packet was lost.

Therefore, to overcome the remaining shortcomings with HTTP/2 and TCP, HTTP/3 was developed. In HTTP/3 the data transmission happens on top of UDP, using a new transport protocol called QUIC (RFC 9000). Like HTTP/2, QUIC splits the transmission to streams, but because it is built on top of unreliable, datagram-based UDP, it does not suffer from the head-of-line blocking problem like HTTP/2 over TCP.

New transport protocol: QUIC

Because QUIC is built on top of UDP, the protocol implementations are done in user plane (although a Linux kernel implementation also exists). This means that even though the protocol is relatively new, there are variety of alternative implementations by different companies and non-profit organizations. For example, the web browsers contain their own QUIC implementation integrated as user-space library.

QUIC transmission is split into frames that are transferred in UDP datagrams. The data content is transmitted in DATA frames, and in addition there are various kinds of control frames for connection and stream management. QUIC also supports unreliable datagrams multiplexed in the same connections with reliable streams, making it suitable also for real-time content.

QUIC integrates datagram-based TLS as part of the protocol in all communication. The TLS negotiation happens together with QUIC connection establishment handshake, making it more efficient than the traditional TCP-based version, where TCP connection establishment needs to be done before TLS negotiation. In some situations QUIC also support 0-RTT connections when previous TLS state is known, allowing fast opening of new connections.

QUIC can apply the same congestion control algorithms as TCP, such as Reno, CUBIC or BBR.

Connection migration

Traditional transport protocols, TCP and UDP, had identified connections through five-tuple: an incoming packet is associated to a connection and its state with source and destination IP address and transport layer port number. This has caused limitations over time, especially as end devices have become mobile and network address translation has become more common. If a host moves to another network, its IP address and connection identification breaks.

QUIC uses separate connection identifier to identify connection between two hosts. This allows for connection migration: If a host moves to another network and starts using a different IP address (e.g. from an organizations WiFi network to a cellular network), the connection can remain usable with the new IP address. If TCP was used, the connection would have become unusable, and a new connection would need to be opened, losing all current connection state and buffered data.

HTTP/3

HTTP/3 resembles HTTP/2 in many ways: it applies binary encoding and QPACK-compressed headers (RFC 9204). Management of streams and connections, and some other HTTP/2 features are done by the QUIC-protocol, however, so the HTTP/3 specification (RFC 9114) just defines the HTTP semantics on top of QUIC.

Fast failover: the Happy Eyeballs method

Incremental deployment of new protocols in the Internet is difficult. There may be years old legacy equipment on the connection path, that do not know how to process new protocol features, and in worst case drop packets with unknown content. In particular, this has been a problem at the waist of the Internet hourglass, the IP protocol. Even though IPv6 was first specified already in the 1990s, its deployment has been slow, because routers along the connection path should be able to process and forward the packets, but many of them are not able to process IPv6.

As we might remember, the DNS database can contain both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses for a DNS name entry, and the name resolution API can be used to query both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses corresponding to a given DNS name, and a list of multiple IP addresses may be available corresponding to a name. Then a TCP or QUIC connection can be established to one of them. If the connection is not immediately successful, learning of the failure can take time, because the transmission protocol tries a number of timer-based retransmissions before giving up. Therefore if the addresses are tried one after another, there may be a significant delay in starting up the communication. Therefore there is a disincentive to even try IPv6 addresses at the end hosts, even though the implementation would support it, because there is a possibility of bad user experience due to failing or delayed connection.

Many end hosts implement a trial method called Happy Eyeballs, however, to test which versions of IP protocol are available from the local host to the destination, and improve the robustness of connection attempts. The idea is simple: the end host opens simultaneous connections using both IPv4 and IPv6 to the destination and checks whether both, or just one one them succeeds. One of the successful connections is selected and others are closed. Implementation may give preference to IPv6 connections, so that whenever IPv6 is available, it will be used.

The QUIC protocol is based on UDP instead of TCP. Unfortunately, the problem with UDP as a connectionless protocol is, that many network middleboxes, such as NATs and firewalls may just drop UDP packets because they cannot reliably track the UDP-based sessions. This will cause a silent failure of QUIC connection establishment in a similar way what would happen with IPv6 if network did not support it. Therefore, in addition to IP address family, whether to use HTTP/3 with QUIC or HTTP/2 with TCP may need to be tested in similar way.

RFC 6555 and different research papers (here is a recent one) report the experiences on Happy Eyeballs method.

Cloudflare maintains the Radar service that measures the current status of protocol deployment. At the time of writing, IPv6 is supported by roughly 40% of connections, HTTP/3 is available for about 1/3 of connections, and HTTP/2 is available for about 2/3 of web connections.

Implementations

Unlike with TCP, where the implementation is included in the operating system kernel and therefore there are in practice a small handful of available implementations depending which operating system is used, for QUIC, that can be implemented as a user-space library, there is a larger variety of implementations. Some of the actively maintained open source implementations (along with the implementation language) are:

- MsQuic (by Microsoft, C++)

- Quiche (by Cloudflare, Rust)

- Quinn (Non-profit, Rust)

- Neqo (by Mozilla, Rust)

- quic-go (Non-profit, Go)

- ngtcp2 (Non-profit, C)

Longer list of implementations is available here.

Further reading

- P. Sattler, M. Kirstein, L. Wüstrich, J. Zirngibl, G. J. Carle. Lazy Eye Inspection: Capturing the State of Happy Eyeballs Implementations. In Proceedings of ACM Internet Measurement Conference (IMC ‘25), October 2025.

Applications of HTTP/3

As HTTP/3 is on top of datagram-based QUIC and UDP with more flexible and performant communication capabilities it allows for different application in addition to traditional web surfing. Many of these are available also for other versions of HTTP, but when operating on top of TCP, the performance may not be ideal because of TCP’s semantics and head-of-line blocking.

Proxying and tunneling

HTTP proxies can be used using the HTTP CONNECT method. When CONNECT request is sent to the HTTP server, it starts forwarding the connections to the given destination. Traditionally this is done for HTTP proxying and fowarding TCP connections, but because HTTP/3 supports use of unreliable datagrams, there are new possibilites. In particular, HTTP/3 can be used for proxying raw IP packets (RFC 9484), effectively using it as a new kind of VPN solution instead of the traditional IPsec-based approach. Such solution may be better compatible with the existing web infrastructure and web-based authentication methods, and has benefits in firewall traversal. Because connections between two hosts are distributed into prioritized congestion-controlled streams, this also allows smooth coexistence with other HTTP/3 traffic.

The MASQUE working group in the IETF is working on various tunneling solutions for HTTP and QUIC, for example proxying Ethernet frames inside HTTP/3 datagrams.

WebTransport

Websockets are used with HTTP to create socket-like semantics for web applications by upgrading an existing HTTP/TCP connection into a socket session. The WebSocket can be operated by a JavaScript application in a browser. The TCP connection turns into a WebSocket session and subsequent requests needs another connection to be opened.

For HTTP/2 and HTTP/3, the more generic WebTransport protocol is defined. The WebTransport sessions leverage QUIC’s prioritized streams to allow multiplexing within same QUIC connection with shared connection state (e.g. for congestion control, TLS security or connection migration). Because WebTransport can use also HTTP/3 and QUIC datagrams with prioritization, it is more suitable for real-time applications such as multimedia or gaming.

The WebTransport protocol development is still in progress in the WEBTRANS working group in the IETF.

Multimedia

Also multimedia transport benefits from HTTP/3 and its real-time capabilities. Typically multimedia is separated into layers of different content encodings of varying quality, that the client request based on the available communication capacity. The concept of streams supports this approach well within a single shared QUIC connection.

The Media Over QUIC (MOQ) working group is currently developing QUIC-based media solutions.