Linux Networking

This section dives into the Linux kernel network stack, describing how the actual TCP/IP protocols are implemented and what kind of optimizations are done to support current high-speed networks. There are also some links to the actual kernel C code in the material, if you are very deeply interested how things are actually done.

If you are interested in more details, without directly diving to code, you may be interested in the seminar proceedings of the “Seminar of Network Protocols in Operating Systems“ we organized here in Aalto University in 2013. It covers various parts of the Linux kernel networking stack, and even though the seminar was more than 10 years ago, the networking implementation in the kernel has not significantly changed and most content in the proceedings is still valid.

This section discusses:

How the network data is organized and buffered in the Linux kernel efficiently, avoiding unnecessary data copying as much as possible

Enabling high-speed data transfer through offloading to network interface card

Use of Netfilter framework for packet processing

Virtualization of networks inside a physical Linux host using network namespaces

Related assignment: “IP Tunnel”

Application-kernel interface

When an user space application calls a system function, such as sendmsg for sending data into a socket, the C library prepares a special CPU instruction (syscall in x86) that switches the processor into kernel mode (programs written in Rust use the same library). The kernel’s syscall entry code receives the syscall number and arguments, looks up the socket, and forwards the call to the correct protocol handler (e.g., tcp_sendmsg for TCP). The networking stack copies data into kernel buffers, builds packets, queues them to the network device driver, and returns. When the kernel finishes processing, it switches back to user mode and the application continues.

Other generic function handlers in kernel include, for example recvmsg (receive data), connect (establishing connection) or init (set up the socket state). The library API may also contain functions such as write or send that don’t have matching counterpart in kernel, but use the same sendmsg interface.

Kernel buffer management

The core packet data structure in the Linux kernel is called sk_buff. It stores a packet’s data buffer, metadata (headers, lengths, protocol info), and pointers as the packet moves through the networking stack from transport layer to network device driver. Related sk_buffs are connected to each other using a bidirectional linked list.

When sendmsg enters the kernel, the send path copies the application data into one or more sk_buff structures, sets up their headers and metadata, and queues them to the socket’s transmit queue. These SKBs then flow through the stack toward the NIC driver, where each layer of the stack adds protocol headers and does other protocol-specific processing.

The below diagram illustrates this process (leaving out many details along the way). If you are interested to see how this works in full detail, links to the source code to the key functions are included below.

In addition to the several control fields in the sk_buff structure, an important part is the data buffer where packet headers and payload is stored. The sk_buff data is preallocated for certain size, and as packets are processed, the data buffer is filled or consumed.

The sk_buff is divided in two parts: the linear data is stored immediately with the sk_buff structure, and has room to store roughly one 1500-byte Ethernet packet, including the headers at different layers. In addition, there is paged data that is a list of typically about 4-kilobyte buffers in separate memory pages. There typically can be up to 16 such fragments, meaning that a sk_buff can hold a maximum of 64 kilobytes of data. This is more than what typical packet in Ethernet carries, but is needed for generic segmentation offloading (GSO), which will be discussed in more detail shortly.

The key pointers to manage the linear part of the sk_buff are:

head: points to the beginning of the data buffer, and is never changed

end: points to the end of the data buffer, and is never changed

data: points to the location where the data processed by the current network layer. The implementation adjusts this pointer as processing moves along the protocol stack and new headers are added. To leave room for adding lower layer headers, some space is typically left between data and head in the beginning when new data packet is created.

tail: the current end of the packet data. If more data is appended at the end of the packet, this pointer is moved forward accordingly.

At the end of the sk_buff there is a shared_info section that contains pointers to the paged fragments, in addition to some parameters related to generic segmentation offloading.

Further reading

- (Very comprehensive) course notes by prof. James M. Westall on sk_buff management from the Protocol Implementation course in Clemson University.

TCP/IP processing

When data is sent to TCP socket, tcp_sendmsg function allocates the needed sk_buffs and adds them TCP write queue. Then TCP checks, among other things, whether congestion window (cwnd) and receiver window (rwnd) allow sending new data in tcp_write_xmit function, and passes segments forward, as permitted by these parameters. Then the TCP header fields are set in tcp_transmit_skb before the sk_buff is passed to IP layer.

On the IP layer the sk_buff is first processed by ip_queue_xmit function. First the function chooses the route for the packet, that determines the network device packet is passed to. The route may have been set by transport layer, or it may have been cached from earlier similar transmissions. If neither of these is the case, the function looks up the correct route from the route table. Then the IP headers fields are set, then the sk_buff is passed to device as determined by the route.

If IP layer is forwarding an incoming packet, the path is a little different, as then the header is already set by the original sender. There are also netfilter hooks at different phases of the IP process that allow custom modules operate on packets, for example for Network Address Translation (NAT) or firewalls.

Network drivers and offloading

When sk_buff arrives to network device driver, the driver prepares descriptors for Direct Memory Access (DMA) of the Network Interface Card (NIC). This allows the NIC to copy the data from kernel memory sk_buffs for transmission. The descriptors are placed in separate NIC transmit queue to wait for actual transmission. When the packet is transmitted, NIC signals the driver that descriptor is free for another packet.

As network speeds have increased, the CPU has become a bottleneck in transmission. Majority of IP packets are 1500 bytes long, as determined the IEEE 802 LAN specifications. On a 10 Gb/s link this means that a packet would be sent every 1.2 µs (excluding link layer overhead). As discussed above, each sk_buff requires quite much processing in the kernel. Therefore modern NICs can take over some tasks traditionally done by the kernel and CPU, for example checksum computation on TCP/UDP and IP layer, or segmentation into actual packets. The latter is called segmentation offloading.

In segmentation offloading the sk_buffs are composed to be larger (typically tens of kilobytes) than the size of one packet, and therefore there are less packet processing at the kernel and CPU. Then the NIC will split the data in the actual packets and prepare the TCP/IP headers for each of them based on the information in sk_buff.

Similar operation can be applied also in receive direction: the NIC can collect multiple incoming packets into a single larger sk_buff deliver up the TCP/IP stack, for similar benefits. This is called Generic Receive Offload (GRO).

Netlink and Configuration Tools

Netlink sockets

Linux uses Netlink sockets to control various attributes related to routes, addresses, network interfaces, Quality of Service (QoS) and many other things. Netlink was designed as a generic message-based control interface between the user space and the kernel using the normal socket API with send and recv system calls reusing the same syscall interface as TCP or UDP. The user processes can send network configuration requests to kernel using the specified asynchronous message interface and kernel can send notifications to user process about interesting network events such as link up/down status or route changes. New features can be easily added without breaking the system call interface.

Netlink socket is opened as any other kind of socket, but with a special AF_NETLINK address family. There are different protocols under this address family, for example (not full list):

NETLINK_ROUTEfor operating on route and link parameters, queueing and traffic classification for QoS.NETLINK_XFRMto manage IPsec associations and policies.NETLINK_KOBJECT_UEVENTfor delivering events from kernel.- etc…

The Netlink messages are type-length-value encoded each message header starts with message length then there is message type (for example RTM_NEWADDR or RTM_NEWROUTE) some flags, and a sequence number to help distinguishing between messages and their responses, and process ID of the user process that sends the message.

If you are interested about the Netlink sockets in more detail, this blog has a detailed example of how the Netlink sockets are used to configure routes.

IP tool

The netlink sockets are rarely used directly. There is, for example, the ip command line tool that provides command line frontend to adjust routes and addresses. Below the hood, the ip tool then uses netlink sockets.

Here are a couple of examples for setting addresses and routes:

Add IP address 192.168.1.100 with 24-bit network prefix to network device eth0. At the same time, a local route to 192.168.1.0/24 is added for eth0:

1

ip addr add 192.168.1.100/24 dev eth0

Adding default route to Internet via host 192.168.1.1. After the previous command, it could be assumed that this host can be found at interface eth0:

1

ip route add default via 192.168.1.1

Network namespaces

Network namespace is an isolated network domain with separate network interfaces, IP addresses and route tables. Network namespace also has isolated firewall rules and socket port allocations. They are a building block for Docker containers, but can be used for various network experimentation needs, for example, to build virtual topologies and isolation for testing and experimentation needs. Mininet is one tool that uses network namespaces to create the emulated network environments.

Namespaces can be connected to each other using veth pairs. veth pair is like a virtual Ethernet cable, each end connected to one namespace. veth can also be connected to virtual switch (e.g., Open vSwitch, ovs), which allows more complex topologies between namespaces, or experimenting with SDN-controlled networks (SDN: software defined network).

Below image shows two namespaces connected to Open vSwitch using veth pairs. Each namespace has its dedicated IP address assigned to network interface eth0 inside the namespace. The native host namespace is called root namespace. The switch operates there, seeing two veth interfaces leading to namespaces (in addition to other possible network interfaces assigned to host).

Example

First, network namespace needs to be added using the IP tool. Here we name our namespace as ns1:

1

ip netns add ns1

Then we create a virtual Ethernet interface pair. One end of the veth interface is titled veth0, and the other end is veth1:

1

ip link add veth0 type veth peer name veth1

One end of the veth interface pair, in this case veth1 is moved under our network namespace ns1:

1

ip link set veth1 netns ns1

We set IP address for veth0 at the host machine (i.e., root namespace), and bring the interface up so that it can be used:

1

2

ip addr add 192.168.76.1/24 dev veth0

ip link set veth0 up

When commands are to be run in a network namespace, they need to be prefixed with ip netns exec ns1 (or whatever happens to be the namespace name instead of ns1). Therefore, to do the same operations as above for setting IP address and activating the interface veth1 that is now under the namespace, we do the following:

1

2

ip netns exec ns1 ip addr add 192.168.76.2/24 dev veth1

ip netns exec ns1 ip link set veth1 up

You could also run any other applications under the namespace in a similar way, for example just ping, some network servers or other applications. The applications do not need to be just command line applications, also graphical applications should work, so you could also run, for example, a web browser in the namespace.

For example running ping across the veth interface to the root namespace:

1

ip netns exec ns1 ping 192.168.76.1

If you know that you will be operating in the namespace for a while, executing multiple commands, you could just start a bash shell in the namespace. Then you don’t need the ip netns exec ns1 prefix with the remaining commands:

1

ip netns exec ns1 bash

Netfilter framework

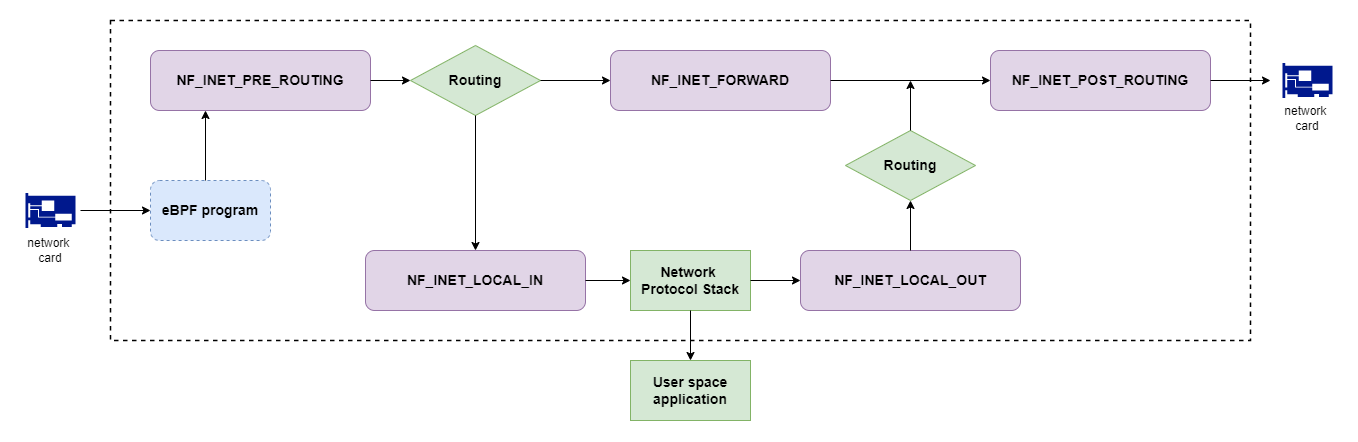

The Netfilter framework provides packet filtering, network address translation (NAT) and connection tracking for Linux. It defines hook points inside the kernel IP packet processing path, where packets can be inspected, modified, dropped or redirected by different extension modules. Netfilter framework provides infrastructure for firewalls, different types of NAT, packet mangling (e.g. for packet marking and QoS), and other kinds of extensions.

There are different hook points at different phases of packet processing:

- PREROUTING: hook is called for packets arriving from network, before routing decision is made.

- INPUT: hook is called for packets that are destined for local host, before delivery to upper layers.

- FORWARD: hook is called for forwarded packets, i.e. when the Linux host works as a router.

- OUTPUT: hook is called when packet is sent by a local process, and arrives from upper layers.

- POSTROUTING: hook is called after routing decision before packet is sent to network, independent of whether packet originated from local host or from elsewhere in the network.

The below picture illustrates the hooks and where they fit the packet processing. It is taken from Chris Bao’s Blog that discusses Netfilter in more detail. Don’t mind about the eBPF in the picture yet, we will come to that a little later.

nftables tool

The nftables tool can be used for setting up various netfilter rules, such as network address translation or filtering traffic. The rules are organized in tables and further in chains, which are an ordered list of tules that packets pass through. Each rule can match certain packet and decide on actions on them. Below are a few examples (note that they need to be run under sudo permissions).

First to create a nftables chain:

1

2

sudo nft add table inet filter

sudo nft add chain inet filter input { type filter hook input priority 0 \; policy accept \; }

To drop all incoming packets from IP subnet 192.168.1.0/24:

1

sudo nft add rule inet filter input ip saddr 192.168.1.0/24 drop

To drop incoming packets destined to TCP port 22 (i.e., ssh):

1

nft add rule inet filter input tcp dport 22 drop

The current configuration can be checked in the following way:

1

sudo nft list table inet filter

Add network address translation from network 10.100.1.0/24 to network interface eth0. This network could be, for example a virtualized container or other separate network namespace in local machine:

1

2

3

4

5

6

nft add table ip nat

nft add chain ip nat postrouting {

type nat hook postrouting priority 100\;

}

nft add rule ip nat postrouting ip saddr 10.100.0.0/24 oif "eth0" masquerade

Typically, when using a NAT to pass traffic from private address spaces to the Internet, the host is forwarding packets from some other sender, for example from a virtual machine, container or namespace. Therefore IP forwarding needs to be enabled in Linux. It is disabled by default:

1

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

Virtual TUN interface

Another type of virtual interface is the TUN interface that can be used for operating with raw IP packets. This is a common method for building tunnels for IP packets, for example encapsulating then inside UDP datagrams across another network interface for passing the packets to another destination that decapsulates the IP packet from inside the UDP datagram. As example use cases, together with encryption, TUN interfaces can be used to build secure virtual private networks, or they could be used for network emulation, if delays or packet losses are enforced on the tunneled packets.

Like the other operations, TUN interface can be set up with the ip tool. First, the interface is created and activated:

1

2

ip tuntap add dev tun0 mode tun

ip link set tun0 up

Then an IP address is assigned and route is added:

1

2

ip addr add 10.0.0.1/24 dev tun0

ip route add 10.0.0.0/24 dev tun0

The IP packets that are sent through the TUN interface can be read in the filesystem from /dev/net/tun device using normal I/O operations, i.e. first opening a file, and then using read call. The call returns the full packet, including the IP header and transport header. Similarly, when writing data back to the network interface, you can use the write call that contains IP header, and then the rest of the packet.

Using TUN interface with Rust

If you are working with Rust, there is a tun crate for providing helpful APIs for the needed operations. See the crate documentation about how to use the library.